Beyond the Pop Label

Duran Duran has often been labeled a “pop band,” a classification that flattens the complexity of their contribution to modern art and culture. Emerging in the late 1970s and rising to international fame in the 1980s, Duran Duran crafted a rich and immersive experience that transcended mere sound. They combined fashion, film, visual art, performance, and cutting-edge technology into a multidimensional expression that aligns closely with the German aesthetic concept of Gesamtkunstwerk—a “total work of art.” Originally coined by composer Richard Wagner in the 19th century, Gesamtkunstwerk describes the unification of various art forms into one cohesive artistic expression. Duran Duran, though operating in the realm of pop music, embody this ideal.

Duran Duran’s commitment to creating a Gesamtkunstwerk is particularly evident in their pioneering approach to music videos.

The New Romantics and the Birth of a Multisensory Art Form

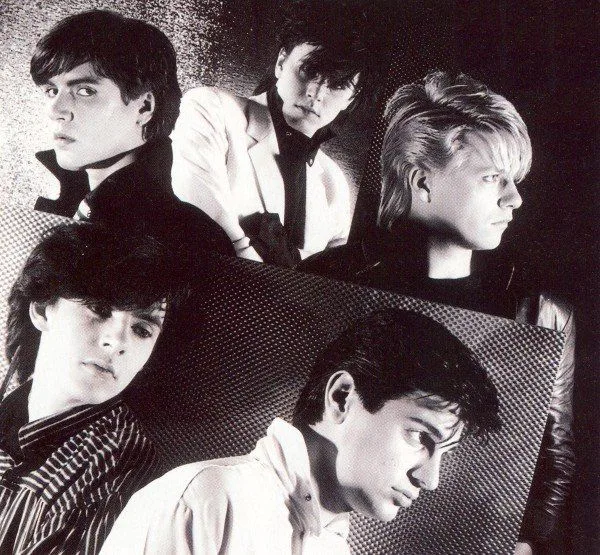

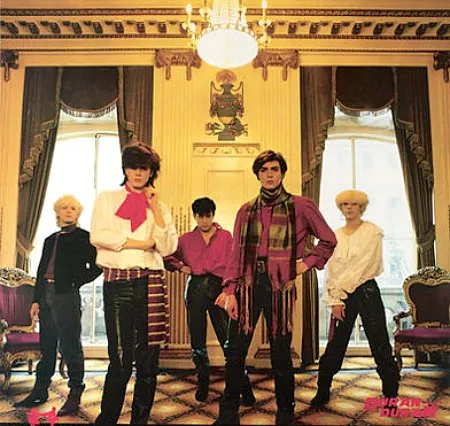

Duran Duran emerged from the New Romantic movement, which originated in London’s club scene around 1979–1981. This movement, rooted in performance, androgyny, glam, and nostalgia, was a conscious rejection of punk minimalism. Bands like Spandau Ballet, Visage, and Duran Duran reintroduced elegance and theatricality to pop culture. However, Duran Duran’s aesthetic extended beyond clubwear and eyeliner.

Their debut single, “Planet Earth” (1981), was both an anthem and a manifesto. With the line “Like some New Romantic looking for the TV sound,” they declared themselves participants in a visual-sound hybrid moment. The Planet Earth video—directed by Russell Mulcahy—introduced a cinematic approach that mirrored science fiction and surrealism. This fusion of fashion, choreography, and artificial environments was not decorative but integral to meaning, situating the band in a visual grammar aligned with Bowie’s theatricality and Roxy Music’s conceptual style.

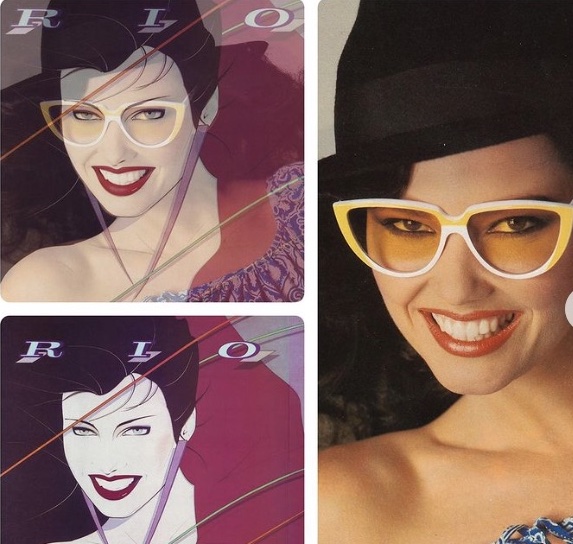

The “Rio” music video demonstrates the holistic artistic approach Duran Duran took in their music videos, embodying the idea of an immersive Gesamtkunstwerk where music, fashion, and visuals work together as a cohesive artistic statement.

Duran Duran’s early work, especially through the lens of Planet Earth, Careless Memories, and Anyone Out There, showcased the height of their stronghold on the New Romantic movement and represented an art-historical moment when music videos became performative canvases, fusing high fashion, visual narrative, and music into a unified aesthetic whole.

Postmodernity and Play in “Is There Something I Should Know?”

By the time “Is There Something I Should Know?” (1983) was released, Duran Duran had mastered the postmodern visual language. The song itself — fragmented, ambiguous, and emotionally ambivalent — was matched by a video that mirrored these qualities. This video disorients rather than narrates, using surreal imagery (blue-painted men, mechanical backdrops, shifting lighting) and rapid montage to break linearity.

In a postmodern context, Duran Duran’s work plays with signs and meanings, refusing a single interpretation. Jean Baudrillard’s theories of simulation and the hyperreal are particularly applicable. Their videos weren’t reflections of reality; they were self-contained realities and simulations that referenced cinema, mythology, fashion, and desire without grounding any of them in truth.

This playfulness of meaning, blurring high and low art, past and present, real and synthetic, marks Duran Duran as true postmodernists. Their commitment to pastiche and surface aesthetics was not shallow but reflective of a broader cultural condition.

EXAMPLE: Andy Warhol’s work exemplifies the postmodern approach to mass production, irony, and commodification. Postmodernism challenges traditional norms of high art.

Narrative, Exoticism, and Myth in Rio and Hungry Like the Wolf

While some critics dismissed Duran Duran’s visual output as indulgent, videos like “Rio” and “Hungry Like the Wolf” demonstrate the sophistication of their storytelling and visual symbolism.

Rio (1982), directed again by Russell Mulcahy, uses the exotic setting of Antigua to construct a dreamlike narrative. The band appears in sleek suits, performing on a yacht—images now iconic. Yet beneath the fantasy lies commentary on glamour as performance, the fluidity of identity, and the colonial gaze. The Caribbean setting becomes a metaphor for escapism, desire, and spectacle. The use of artifice (painted women, pop colors, staged glamour) heightens rather than conceals the idea that identity itself is constructed.

Hungry Like the Wolf (1982) furthers this with its Indiana Jones–style adventure aesthetic. Shot in Sri Lanka, the video juxtaposes primal desire with colonial imagery and cinematic references. Le Bon’s pursuit of a femme fatale through jungles and markets reads like a mythological quest. But again, this is myth as mediated through fashion and film—it is the performance of desire, not desire itself.

The visual language here is not background to the music but integral to the song’s meaning. The exotic locations are not simply scenery; they become part of the band’s commentary on power, gender, and fantasy. This aligns closely with the Gesamtkunstwerk model: music, costume, performance, and cinematic narrative work together to create an immersive, multisensory experience.

The Wild Boys: Industrial Fantasy as Art

With “The Wild Boys” (1984), Duran Duran pushed the boundaries of video art into full-blown dystopian spectacle. Directed by Mulcahy and inspired by William S. Burroughs’ book of the same name, the video features mechanical contraptions, dark water tanks, leather costumes, and surreal torture devices—all wrapped in a brutalist industrial aesthetic.

Nick Rhodes, the band’s keyboardist and visual architect, once described the video as “a visual playground of nightmares and futurism.” This is a key moment where music video crosses into performance art. The Wild Boys video is closer to the work of Matthew Barney than traditional pop—blurring body, technology, violence, and fetish.

Every detail—from the wind machines to the prosthetics and prosthetic-enhanced monsters—is curated with artistic precision. The performance of the song is secondary to the environment in which the performance takes place. This visual world does not serve the music; it is the music, realized in physical space.

Fashion as Art: Identity and Surface

Fashion has always been central to Duran Duran’s identity, not as a marketing ploy, but as an artistic practice. They collaborated with designers like Antony Price and Kahn & Bell, whose work sat at the intersection of sculpture, fabric, and provocation. Their evolving looks—from pirate shirts to crisp tailoring—were more than trends; they were artworks in themselves, each era of the band carefully costumed to reflect evolving themes.

Fashion functioned as semiotics — colors, cuts, and styles communicated identity and emotional tone. In this way, the band aligns with visual artists like Cindy Sherman and Gilbert & George, who used self-presentation to question authenticity and performativity.

Their later collaborations with stylists like Arianne Phillips and designers such as Vivienne Westwood continued this integration of fashion and meaning. Wardrobe was not decoration; it was narrative, mood, and message—a continuation of their Gesamtkunstwerk.

Warhol’s portraits of Monroe highlight the constructed nature of celebrity identity, which parallels Duran Duran’s strategic manipulation of their own public personas, demonstrating the postmodern manipulation of identity in both art and culture.

Photography, Album Art, and the Gallery Gaze

Duran Duran’s album covers and promotional photography, often crafted with art photographers like Malcom Garrett, Denis O’Regan and artists like Patrick Nagel, contributed further to their visual mythology. The Rio album cover (1982), with its bold lines and Art Deco styling, instantly communicates themes of fantasy, elegance, and stylized femininity.

Patrick Nagel’s illustration for Rio is now part of pop art iconography, comparable to Warhol’s Marilyns or Lichtenstein’s comic women. These images were not passive packaging—they were intentional art pieces, contributing to the band’s Gesamtkunstwerk vision.

Their 1993 self-titled “wedding album,” featuring photos of their parents’ wedding days, presented a deeply postmodern juxtaposition of private and public, family and fame. It challenged the myth of pop artifice by inserting sincerity and origin. As a visual gesture, it invites the gallery gaze and rewards critical analysis.

Soundscapes, Synths, and Technology

Musically, Duran Duran were early adopters of synthesizers, sequencers, and digital sampling, innovations that changed the possibilities of pop production. Nick Rhodes in particular treated the synthesizer not as a background instrument but as a painter’s palette, creating emotional landscapes rather than simple hooks.

Their use of studio production as a compositional tool parallels developments in visual art—digital collage, layering, fragmentation. Songs like “The Chauffeur” or “Save a Prayer” unfold like sonic installations, filled with spatial effects and textural nuance. These are not mere tracks; they are immersive environments, precursors to the ambient installations of artists like Brian Eno or the sonic sculptures of Janet Cardiff.

Duran Duran as Living Art: The Enduring Gesamtkunstwerk in a Multimedia Age

As technology evolved, so did the band’s approach to art.

Unlike many of their contemporaries, Duran Duran has remained active and visually ambitious into the 21st century.

In the 1990s and beyond, they embraced the digital age, using the internet and new media platforms to expand their artistic vision. Their 1997 album Medazzaland and 2015’s Paper Gods saw the band experimenting with new technologies, collaborating with contemporary artists and musicians, and incorporating digital elements into their work. Videos such as Girl Panic! (2011), featuring supermodels in meta-performances, and Invisible (2021), which used artificial intelligence for its visuals, continue their engagement with evolving technology and conceptual art.

In the 21st century, Duran Duran’s multimedia presence has remained as integrated as ever, with the band continuing to release visually stunning albums, produce high-quality music videos, and perform live shows that blur the lines between music and theatrical performance. They have also continued to collaborate with visual artists, filmmakers, and designers, maintaining the Gesamtkunstwerk ideal while adapting to the technological innovations of the digital era.

Notable Artists in Postmodernism and Gesamtkunstwerk

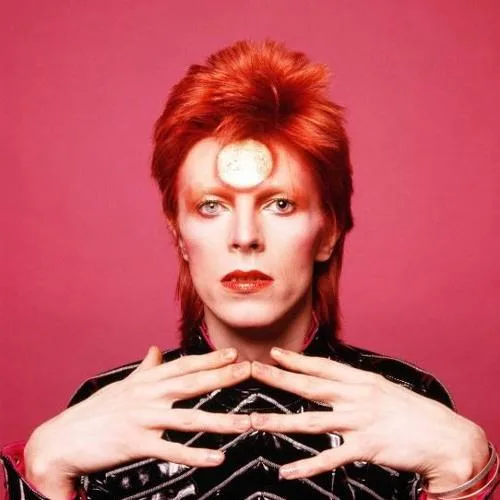

In music, postmodernism’s embrace of eclecticism and fragmentation can be seen in the work of bands such as Talking Heads and David Bowie. Talking Heads, particularly on albums like Remain in Light (1980), merged elements of funk, punk, and world music to create a sound that was both avant-garde and highly accessible. David Bowie, too, embodied postmodernism’s playful, fluid approach to identity, famously reinventing himself through various personas such as Ziggy Stardust and the Thin White Duke. His ability to blend music with visual art, theater, and fashion made him a quintessential postmodern artist. Duran Duran’s embrace of eclecticism and visual storytelling is directly influenced by these figures, who pioneered the integration of music with other art forms, thus laying the groundwork for the Gesamtkunstwerk in pop music.

Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust persona is a powerful example of how the New Romantic movement integrated music, fashion, and theatricality. Ziggy captured the fluid, performative nature of identity.

The fusion of art, fashion, and music also emerged through designers like Jean-Paul Gaultier and Vivienne Westwood, whose work embodied a distinctly postmodern sensibility. Gaultier’s designs — marked by gender fluidity and pop culture references — challenged traditional aesthetics, much like Duran Duran’s blend of style and sound disrupted expectations of mainstream pop. Similarly, Westwood’s punk-inspired fashion, with its mash-up of historical references and subversive flair, mirrored a broader cultural move toward irony, playfulness, and the deconstruction of norms.

This interdisciplinary spirit aligns with Richard Wagner’s original concept of the Gesamtkunstwerk. Wagner’s vision of unifying music, drama, and visuals into a single immersive experience influenced later figures like Robert Wilson, whose experimental theater blurred the lines between visual art and performance. Marina Abramović pushed this further by transforming audience interaction into part of the art itself, as seen in The Artist is Present (2010). Like Duran Duran, these artists operated across mediums, creating integrated experiences that redefined how audiences engaged with art.

Synthesis and Significance: Duran Duran’s Legacy at the Crossroads of Postmodernism and Gesamtkunstwerk

In positioning Duran Duran as Gesamtkunstwerk, we acknowledge their status not just as musicians but as multimedia artists. Their integration of music, narrative, fashion, visual art, and technology represents a holistic approach to creation that aligns with the highest ideals of interdisciplinary art.

To engage with Duran Duran is not simply to listen but to enter a world—a curated, coded, richly symbolic world that rewards both emotional immersion and intellectual inquiry. In the gallery of modern art, Duran Duran deserve a room of their own.

Duran Duran’s legacy is a powerful example of how postmodernism and the Gesamtkunstwerk can coexist and reinforce each other. The band’s approach to music, fashion, video, and performance represents an ongoing attempt to reconcile fragmentation with unity, offering a total artistic experience that continues to captivate audiences. By integrating a wide range of artistic influences and mediums, Duran Duran has crafted a body of work that is as multifaceted and complex as the postmodern condition itself.

Their ability to adapt to new media and cultural shifts while maintaining a consistent artistic vision has solidified their place in both musical and cultural history. As such, Duran Duran’s work continues to serve as a model for how artists can embrace postmodern fragmentation without losing sight of a unified artistic purpose—creating a true Gesamtkunstwerk for the modern age.

References and Sources:

- “Postmodern Art: A Brief Introduction.” Art History Resources. https://www.arthistoryresources.net/postmodernism

- “The Rise and Influence of David Bowie.” Rolling Stone. https://www.rollingstone.com/music/artists/david-bowie

- “Andy Warhol: The Art of Mass Production.” MoMA. https://www.moma.org/artists/5665

- “Marina Abramović: The Artist is Present.” Guggenheim Museum. https://www.guggenheim.org/artwork/28359

- Hebdige, D. (1979). Subculture: The Meaning of Style. Routledge.

- Frith, S., & Horne, H. (1987). Art into Pop. Methuen.

- Rimmer, D. (1985). Like Punk Never Happened: Culture Club and the New Pop. Faber.

- Le Bon, S., Rhodes, N., Taylor, J., & Taylor, R. (1984). Duran Duran: Sing Blue Silver [Documentary].

- Somerset House. (2015). Duran Duran: The Visual Legacy. https://www.somersethouse.org.uk/whats-on/duran-duran

- “Rio” (Music Video, dir. Russell Mulcahy). 1982. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e3W6yf6c-FA

- “The Wild Boys” (Music Video, dir. Russell Mulcahy). 1984. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M43wsiNBwmo

- Interview with Nick Rhodes. (2004). The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/music/2004/oct/22/popandrock.duranduran